Brodsky/Baryshnikov

a theater piece written and directed by Alvis Hermanis

New Riga Theatre, Riga, Latvia, October 15–November 7, 2015

Baryshnikov Arts Center, New York City, March 9–19, 2016

Leonid Lubianitsky

Joseph Brodsky and Mikhail Baryshnikov, New York City, 1985

Leonid Lubianitsky

Joseph Brodsky and Mikhail Baryshnikov, New York City, 1985

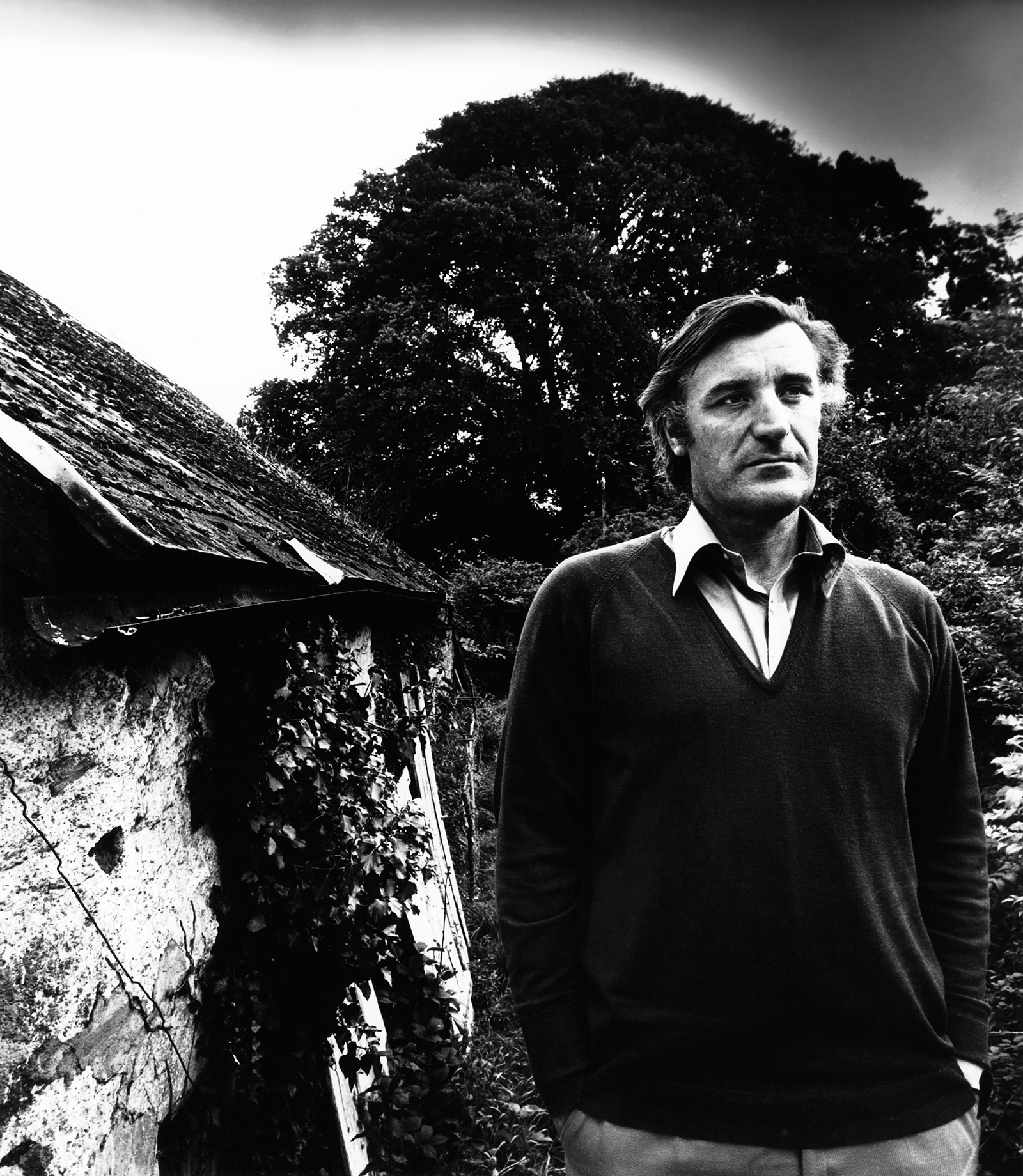

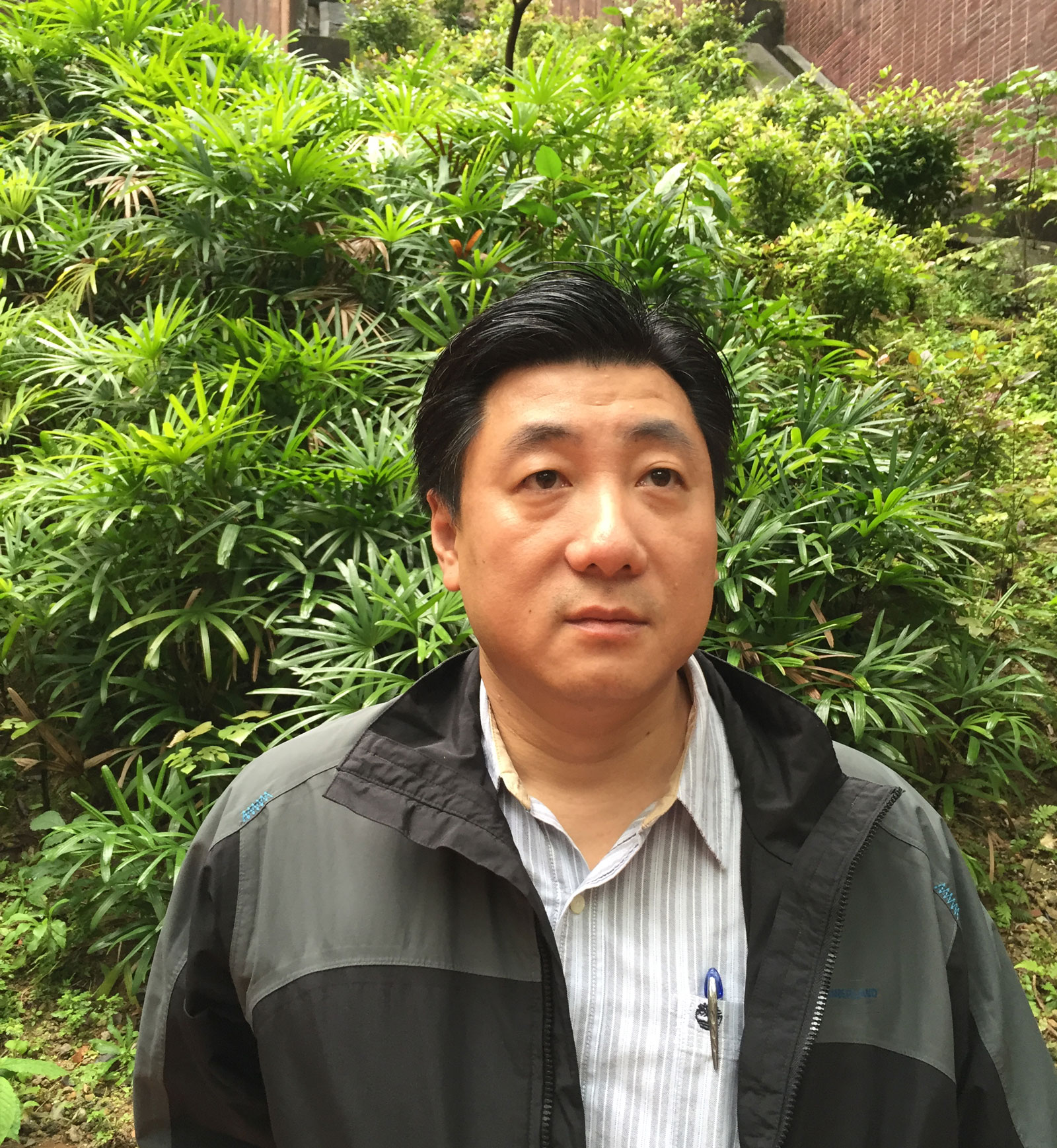

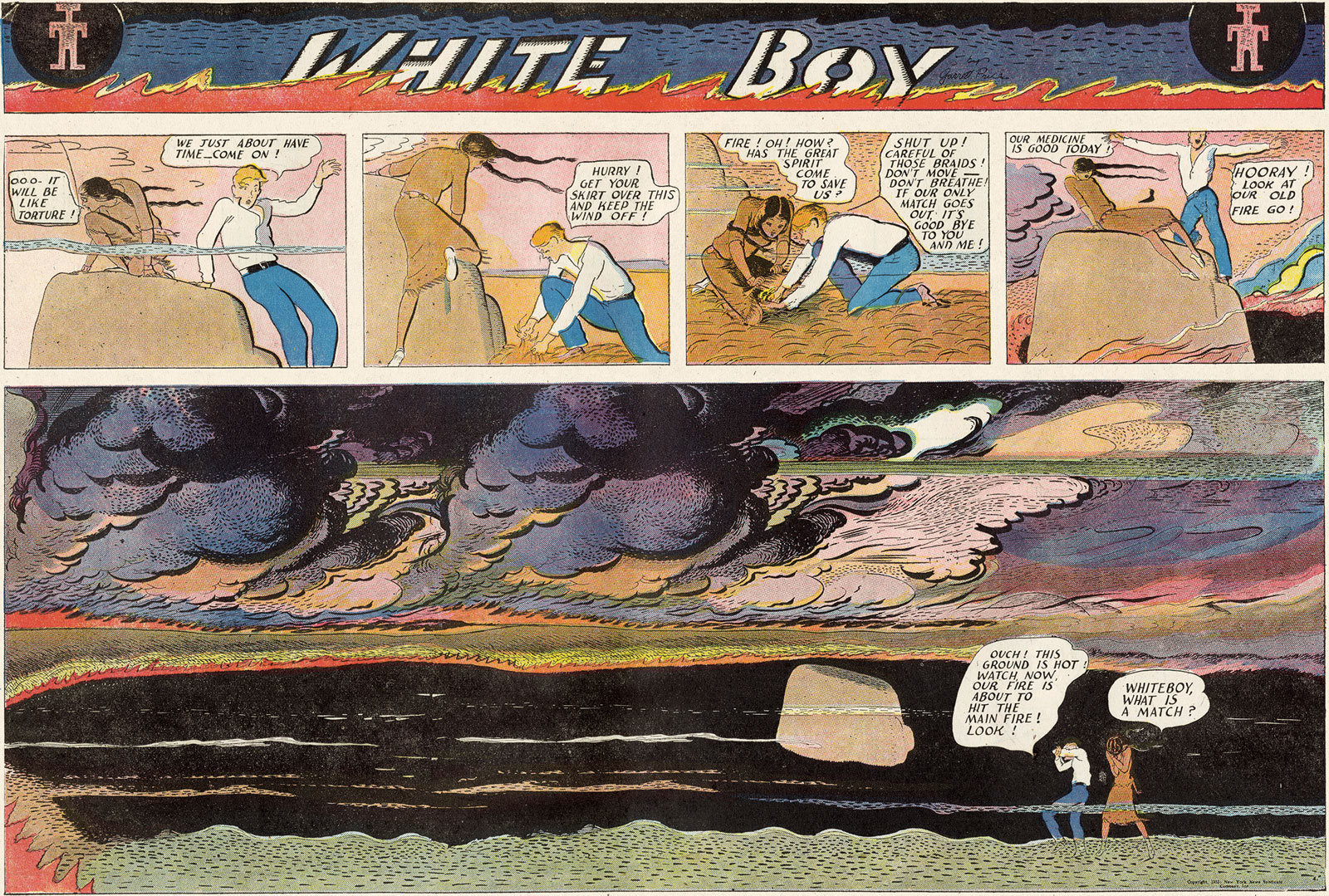

Many emotions are entwined in the theater piece Brodsky/Baryshnikov, which had its premiere at the New Riga Theater in October and will open at the Baryshnikov Arts Center in New York in March. Its subject is Joseph Brodsky, who was born in Leningrad in 1940 and died in Brooklyn in 1996. Other Russians of Brodsky’s time—notably his great elders Anna Akhmatova, Osip Mandelstam, Marina Tsvetaeva, and Boris Pasternak—were made to feel more keenly than he their government’s scorn for artists, but his case too is notorious. Soon after he began circulating verse in samizdat in his late teens, he came under the eye of the authorities. He was denounced in a Leningrad newspaper in 1963 as “pornographic and anti-Soviet.” In 1964, he was tried for “social parasitism” and sentenced to five years’ hard labor.

He landed in the small village of Norenskaya, in the Arkhangelsk region of the Arctic. By day he chopped wood and hauled manure. By night he taught himself English, and read English and American poetry—above all, John Donne, Robert Frost, and his idol, W.H. Auden—in his hut. He later said that this was one of the happiest times of his life. Meanwhile, the transcript of his trial had been smuggled to the West, and his case became an international scandal. Embarrassed, the Brezhnev government released him after only a year and a half.

This did not mean that he was free, however. By then, because of the trial and because of poems of his that were being published in the West, he was a famous man. When literary dignitaries came to Russia, he was often the person they wanted to meet. But he could not get a poem published in the Soviet Union, not to speak of obtaining permission to attend literary conferences outside the Soviet Union. This is the sort of tragicomedy in which the USSR specialized. The authorities eventually tired of it, though, and one day, in June 1972, he was simply taken to the airport and put on a plane.

He did not know whether the plane was going east or west. It went west, to Vienna, and at the airport he was met by the American Slavist Carl Proffer, whom he knew, and whose small press, Ardis, in Ann Arbor, Michigan, would publish a number of his writings in Russian. Auden had a second home outside Vienna, and the day after Brodsky’s arrival Proffer rented a car and deposited Brodsky there, to what was apparently Auden’s surprise. Brodsky stayed for four weeks. Auden got him some money and called various people to say that he was coming.

Proffer arranged for him to be given a job as poet in residence at the University of Michigan, where he himself taught. In July 1972 Brodsky flew to the United States, where he would live until his death twenty-three years later. Almost always, he taught—after Michigan at other schools, above all, Mt. Holyoke, where he became a chaired professor. Over the years he received just about every important award a poet could want, culminating in the Nobel Prize in 1987.

Two years before Brodsky turned up on his doorstep, Auden had written a foreword to a collection of the Russian’s poems, translated by George Kline. Brodsky, Auden said, was

a traditionalist in the sense that he is interested in what most lyric poets in all ages have been interested in, that is, in personal encounters with nature, human artifacts, persons loved or revered, and in reflections upon the human condition, death, and the meaning of existence.

This seems rather soft-spoken, but it is accurate. Brodsky was not a modernist in the sense of embracing the absurd or expressing weariness. Quite the contrary. He pursued the “great themes,” energetically.

And because of what he saw as the gravity of his subject matter, he hated any looseness in a poem. He said that the poet Evgeny Rein, a friend of his, taught him:

if you really want your poem to work, the usage of adjectives should be minimal; but you should stuff it as much as you can with nouns—even the verbs should suffer. If you cast over a poem a certain magic veil that removes adjectives and verbs, when you remove the veil the paper still should be dark with nouns.

Dark with nouns: what a phrase! It reminds me of the frames that beekeepers use. When you pull one of the frames out of the box, it is thick with bees, clotted with them. The note of menace here is also true to Brodsky. In an interview for The Paris Review he told Sven Birkerts that one thing he loved about Robert Frost was his restraint, “that hidden, controlled terror.”

He too showed a hidden terror, and long before his trial the Soviet Union had given him cause. As a small child he nearly died of starvation during the siege of Leningrad. Because the family was Jewish, his father, a photographer, lost his job during Stalin’s onslaught against the Jews in the early 1950s; the family was supported, barely, by his mother’s clerical work. Partly to help out, Brodsky quit school at fifteen and took various low-level jobs, including, at one point, cutting and sewing bodies in a prison morgue. He fell in love with a painter, Marina Basmanova, but soon his friend and fellow poet Dmitri Bobyshev was also in love with Basmanova. That was when the denunciations began—a fact from which people have drawn conclusions about Bobyshev’s responsibility. Brodsky was twice detained in psychiatric hospitals. Then came the trial, the “internal exile” in Norenskaya, and, ultimately, the expulsion.

In his autobiographical essay “Less Than One,” first published in these pages, Brodsky records a memory from 1945, when he was five. He and his mother were in a train station, which was bedlam, because the war was just over and people were trying to get home:

My eye caught sight of an old, bald, crippled man with a wooden leg, who was trying to get into car after car, but each time was pushed away by the people who already were hanging on the footboards. The train started to move and the old man hopped along. At one point he managed to grab a handle of one of the cars, and then I saw a woman in the doorway lift a kettle and pour its boiling water straight on the old man’s bald crown.*

Another writer might well have expatiated on the pain of witnessing such a scene. Brodsky does not. For that modesty as well as his tremendous poetic powers he was cherished not just as an artist. He was a moral hero, to many people.

One was Alvis Hermanis (born in 1965), who is an important man in European theater. Hermanis started as a movie actor in his native Latvia. Now he is a director and works very widely across Europe, especially in German-speaking theater and in opera. (He just directed a Damnation de Faust at the Paris Opera. In 2018 he will stage Lohengrin at Bayreuth.) Since 1997 he has also been the head of the New Riga Theatre, a playhouse that opened, under that name, in 1902. In later years it was put to various uses by Nazis and Communists, but in 1992 it reopened as a repertory theater.

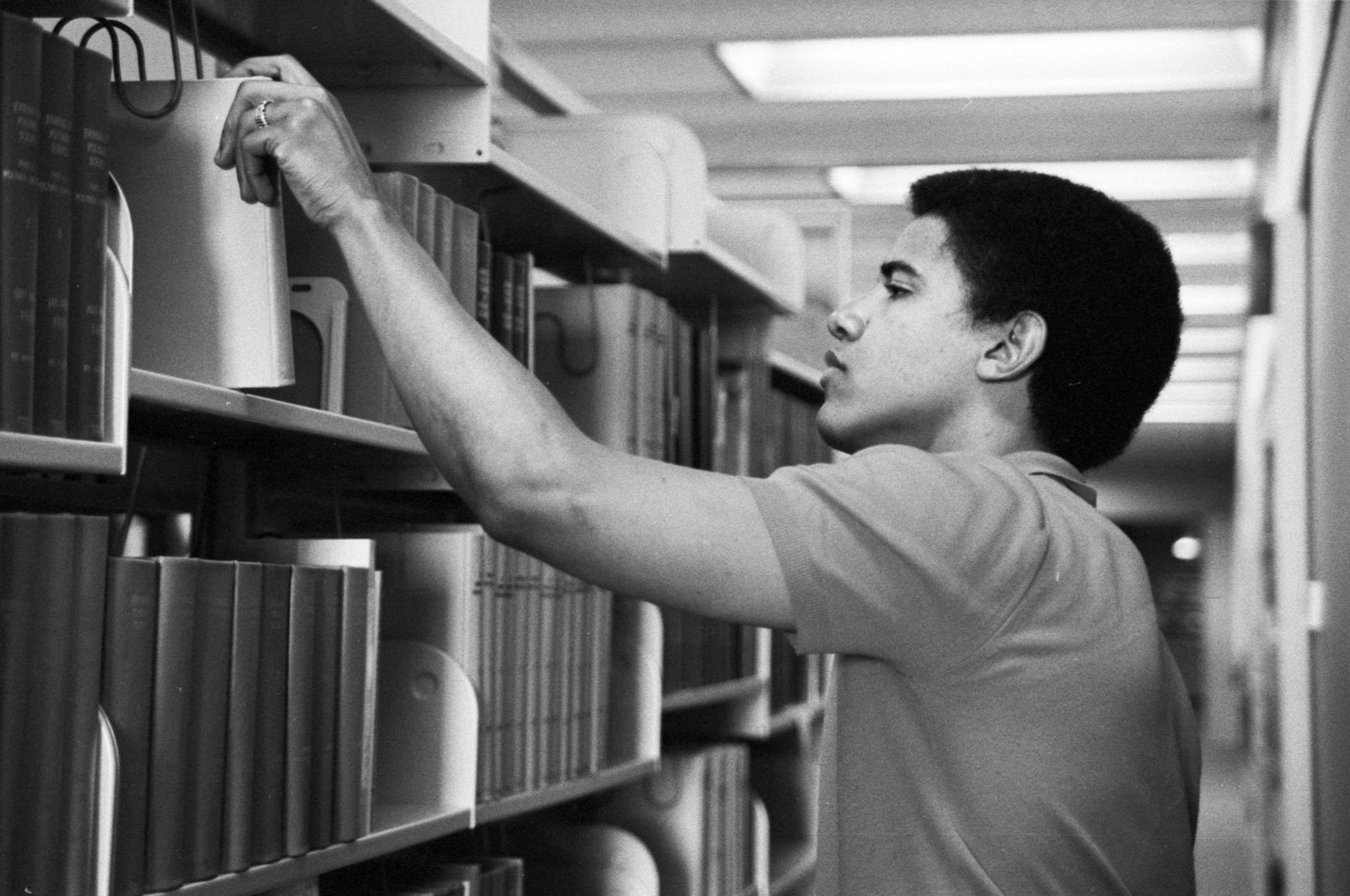

In the early 1990s, Hermanis was invited to perform in New York, and he stayed in the United States for two years. It was a difficult time for him. In his words, “I put my head in a washing machine.” He worked in New York for a year. Then he moved to San Diego, where he lived in a welfare hotel and communicated with no one. (“It was very cruel to my parents. For six months they did not know where I was.”) He spent every day, all day, in the San Diego Public Library, reading books that were forbidden in Latvia during Soviet times. This is when he encountered Brodsky’s poetry. He was overwhelmed by it. One day, at closing time, he could not bear to part with his Brodsky book, so he decided to steal it. “I did not know that they had put those little chips in the books. So when I tried to leave, many bells rang. I was so humiliated. I had to take this book out of my pants.”

Reading Brodsky, Hermanis says, is not just a mental but a physiological experience. “All those images have to do with physical sense, and it is physically painful, almost, to read him.” In this regard, he compares Brodsky to Chekhov, but he says that Brodsky is worse:

He is like a surgeon who is cutting with a knife your belly and looking straight in your eyes. He is killing you, and he is telling you. I had never before read a writer who has so no hope, who gives not the slightest chance. Whatever illusions you had, Brodsky makes you say goodbye to them. And so you achieve a sort of Buddhistic calm.

Hermanis conceived Brodsky/Baryshnikov as a tribute to Brodsky, but as the title indicates, he wrote it to be performed by only one man.

Mikhail Baryshnikov is a favorite son of Riga. Both his parents were Russian, but after the war the Soviet Union was faced with a drastic housing shortage, and the outlying territories were forced to take in many Russians, including Lieutenant Colonel Nikolay Petrovich Baryshnikov, who taught military topography, and his wife, Aleksandra Vasilievna. Mikhail Nikolayevich was born soon afterward, in 1948, and lived in Riga until, when he was in his early teens, his mother died (by suicide), his father remarried, and his ballet teacher—he had started lessons at age nine, at his mother’s behest—decided that he had progressed beyond the training that Latvia could give him. He needed to go to Leningrad, to the Kirov Ballet’s Vaganova Institute.

By the time Baryshnikov graduated from the Vaganova Institute and joined the Kirov in 1967, Brodsky had already returned from Norenskaya, and for the next seven years the two men lived in the same city. Baryshnikov knew Brodsky’s poetry, but the two men did not meet, and if they had, it wouldn’t have been good for Baryshnikov. Brodsky was a dangerous person to be seen with.

By this time, furthermore, Baryshnikov too was under suspicion, as a defection risk. In 1972, Brodsky was thrown out of Russia, and two years later Baryshnikov threw himself out. On tour in Toronto, he walked out of the stage door after a performance, signed some autographs, and then, instead of getting into the company bus, he turned and ran. A getaway car, arranged by friends, was waiting a few blocks away. He was now a Western artist.

In a long interview that he recently gave to the Latvian magazine Laiks, Baryshnikov recalled that he met Brodsky soon afterward, at a party at Mstislav Rostropovich’s house. “Joseph was sitting on a couch. He looked at me and said, ‘Mikhail, come sit down. There are things to talk about.’” Baryshnikov, though a celebrity, considered Brodsky a far greater celebrity. “My hands were shaking. The cigarette was going back and forth, like this,” he says, waving his hand like a windshield wiper. He sat down, and they talked for a long time. Thereafter they were friends for over twenty years, until Brodsky’s death. They spoke to each other every day.

In Brodsky, born eight years before him, Baryshnikov acquired a kind of older brother, and he needed one. Though a number of people were very kind to him, he did not, at this early point, have close friends in the United States, and he was slow in making them, because he had no time to study English. With Brodsky he could speak in Russian, and they had a city, a government—in some measure, a history—in common. “Over the years that we spent together, he really set me on my feet. I acquired a kind of certainty.” In addition to his lodgings in Ann Arbor, Brodsky eventually found an apartment in New York, on Morton Street in Greenwich Village. When he was in town, he and Baryshnikov would take walks along the nearby Hudson River.

Or we’d drink whiskey or we’d talk about girls or whatever—anything—and it was a real release for me. His house was so cozy. And there were always interesting people: Czesław Miłosz, Derek Walcott, Stephen Spender, Susan Sontag. He got me to read Russian classical literature that I hadn’t had time for when I was in Russia. I couldn’t yet talk to him very seriously about poetry, but I knew some poems by heart—Baratashvili, Mandelstam—and he would get me to recite them.

He was a stern judge. When he didn’t like something that I was doing, he’d say so. I remember, I did some sort of performance, a piece by Maurice Béjart, and there I’m dancing a solo of Hamlet in an empty café, and I recite “To be or not to be”

—this was Béjart’s Hamlet, to Purcell and Duke Ellington—

and then I throw down Yorick’s skull. Joseph saw this on TV, and when I saw him next he said to me, “We have to talk.” We went to a café and he said “Maybe you shouldn’t be doing this ballet because—what are you doing? It’s so vulgar.” He would say to me, “Be good.”

Baryshnikov was charmed by Brodsky’s vivacity, his capacity for fantasy and play, his readiness to love things. Brodsky loved water—he loved oceans, rivers. He adored Venice—he wrote a book on it, Watermark—and the Venetians made him an honorary citizen. He loved cats. (When he was young, he and his parents had a game where they would converse in a sort of cat-talk, meows in various registers.) He said that if he had to live another life he would like to be a cat in Venice, or even a rat. (He called Baryshnikov Mysh, or Mouse.) He cared about world events, and he hated to miss the evening news. He was a skirt-chaser, and women were crazy about him, too. (“He rarely left a party alone,” says Baryshnikov.) The prospect of his birthday thrilled him, and he would always stage a huge feast. “People came from faraway cities,” Baryshnikov recalls. “The place was packed. They partied all night long.” Baryshnikov, by contrast, was always rather embarrassed by his birthday. But Brodsky would bring him a book, with an inscription in it. In his interview with Laiks, Baryshnikov pulled one of the birthday books off his shelf and read the inscription:

Mysh is forty-three.

He has dumplings inside him.

His knee hurts.

There’s a fire burning in the hearth,

There’s smoke coming from the hearth.

And we’re siting here drunk.

“It rhymes,” Baryshnikov says.

Janis Deinats

Mikhail Baryshnikov in Brodsky/Baryshnikov

Janis Deinats

Mikhail Baryshnikov in Brodsky/BaryshnikovAs the lights go up on Brodsky/Baryshnikov we see a small glass house, nine feet by eighteen, with a front door and a back door, sitting in the middle of an otherwise empty stage. The house is in Art Nouveau style—it looks as if it had been made by the French Art Nouveau architect Hector Guimard—but with certain odd features. Next to its front door, for example, is a dirty old fuse box that periodically spits out frightening sparks. Also, there is some sort of blackish moss creeping down the wooden strips that join the glass panels.

The music adds to the strangeness. There seems to be a sort of distant chorus, but sounding an unvarying note, plus, in the foreground, a noise of crickets. (This becomes more strange when you find out later that the distant chorus is also a recording of crickets, but very, very speeded up.) Both elements—the set design, by Kristīne Jurjāne, and the score, by Oļegs Novikovs and Gatis Builis—are elegant and sinister at the same time.

A man, Baryshnikov, appears at the back door carrying a small suitcase. You can tell that he has never been here before and that, in the manner of a fairy tale, he doesn’t know whose place this is, or what it is. He walks into the house, comes out the front door, pulls out a cigarette, bites off the filter (Brodsky used to do that), pats himself down to locate a pack of matches, finds none, and unhappily replaces the cigarette in its box. He opens the suitcase and takes out an alarm clock, a couple of books, and a pint of Jameson (Brodsky’s drink of choice). He puts on his glasses, opens one of the books, and begins reading a Brodsky poem. The rest of the play’s text flows from there: forty-four Brodsky poems, mostly unabridged, not at all in chronological order. (The one that ends the play was written when he was seventeen.) The poems were all chosen and arranged by Hermanis. They are spoken in Russian, with supertitles scrolling up the cornice of the glass house. (In Riga, the supertitles were in Latvian; in New York, they will be in English.)

I asked Hermanis whether he hadn’t worried that his show would turn out to be static—a poetry reading. He said no.

I had a story in my mind, that the play would be about a meeting between two people who had been closest friends for twenty years, and then one died. The performance would be like a spiritist séance. Direct communication with the audience is not our goal. Audience is not necessary. Audience is able just to witness.

Baryshnikov designed all the more elaborate movements, and he gives us a lot to look at. He spins, he stands on the chair, he strikes classical poses, he checks his teeth, he drinks the Jameson, he takes his clothes off and puts them on. He is constantly moving in and out of the house and thus from a state of firm reality to a sort of watery, dreamlike image as we watch him through the glass. During the recitation of “The Butterfly,” he chases an invisible butterfly and then, wittily, turns into one. During a beautiful poem about a horse, he does a brief flamenco dance, his chest as high and proud as a horse’s. There is a crisis. In the course of the poem “Portrait of Tragedy” he undergoes a grotesque series of convulsions. He stabs his navel so hard—he is shirtless here—that you think he is really going to harm himself.

But the main drama is in the use of the language. Sometimes Baryshnikov reads the poems from one of the books; sometimes he whispers the words, sometimes he yells them, sometimes he just opens his mouth and lets them fall out. Usually he speaks them from memory. Unnervingly, sometimes Brodsky reads the poems, over the sound system. (At those times, an old reel-to-reel tape recorder turns on one of the benches.) But then sometimes Baryshnikov too reads the poems on tape, and you’re not always sure which of them is speaking. Brodsky chants his poems, as some poets do, and Baryshnikov too chants, and davens, as if reciting a Jewish liturgy. Hermanis told me that Baryshnikov did this without being directed to, and that it is natural to people reciting poetry. It is part of poetry’s shamanism, he says.

Great dancer that Baryshnikov is, he has always been a considerable actor as well, and the treatment of the language is the most impressive thing in the show even, probably, to those who are getting it from the supertitles. Many knowledgeable people say that Brodsky’s poetry loses a huge portion of its power when it is not in Russian. “How could anyone who had not read him in Russian understand him by his English poems?” asked Isaiah Berlin, speaking, I believe, both of the poems that Brodsky wrote in English (he tried) and of English translations from Russian, both by him and by expert translators, often working with his help. “It’s utterly incomprehensible. Because there is no sense that they were written by a great poet. But in Russian,…from the very beginning, as soon as it starts, you are in the presence of genius.” Brodsky himself seemed to admit the problem. He called himself “a Russian poet and an American citizen.” His friend Lev Loseff, who taught in the Russian department at Dartmouth for thirty years, said in his masterful book on the poet that Brodsky won the Nobel Prize not for his poems, but for his essays, most of which he wrote in English.

Alvis Hermanis says that he knows Brodsky’s work in translation and that “there is no way to compare it to what he did in the Russian language.” But this does not discourage Hermanis. Remember his statement that reading Brodsky’s poetry is a physiological experience. In Brodsky’s mind, he says, language “bubbles, it scratches, it never stops.” And the play aims to show that.

As much as I am interested in the sense of the poetry, I am interested in the sound—how it goes through the body, sensual, erotical, or like an electrocution. Misha was interested in that, too, and willing to show it. The play is a real striptease. Misha is brave, he is crazy.

For both men, this is no doubt related to what is said to have been Brodsky’s belief that poetry was not something contained in a language as much as it was, itself, a language, speaking truths found only there, and which you ignore at your peril. Indifference to poetry, he felt, underlay the Soviet Union’s political crimes. In the Paris Review interview, Brodsky told Birkerts that his main interest was “the nature of time…what time can do to a man.” By which he seems to have meant not just that time kills us; it may also efface any sign of our passing on this earth.

Of the poems that Hermanis collected for his play, the most moving, I think, is “Letter to a Wall,” written by Brodsky when he was leaving his job at the prison morgue. “Keep my shadow,” he says to the wall. “Keep my shadow. I don’t know why./Preserve my shadow. I cannot explain. I’m sorry./It is important now. Preserve my shadow.” Of course, a shadow is a thing that may vanish instantly, and the people passing this particular wall—criminals, madmen—would have been most unlikely to be memorialized. That is why he chose the wall. He was twenty-four, and his trial was coming up in four months. He was afraid of being extinguished.

In 1990, Brodsky got married, to Maria Sozzani, an Italian woman with some Russian ancestry as well. She was twenty-two years younger than he. They had a child, Anna, in 1993. But he was already in poor health. “It’s hard to walk the length of a building,” he wrote to a friend late in 1995. A month later, his wife went to his study in the morning and found him dead on the floor, of his fourth heart attack, at fifty-five. He was buried in Venice.

At the end of Brodsky/Baryshnikov Baryshnikov packs his things back into the suitcase and heads out the back door of the little glass house. But something strange has appeared right beyond the threshold: a big, bushy green fern. It wasn’t there when he arrived, or it wasn’t lit so that we could see it. The play has been about a dead man, or a man visiting a dead man. He should not, at the end, be faced with this robust greeting from Mother Nature. Maybe Hermanis is saying that Brodsky was right: that there is some truth-beyond-truth that poetry, and nothing else, confers. Maybe if, in Hermanis’s words, you let yourself be electrocuted by Brodsky, you don’t die. You start to live.

For information about the Joseph Brodsky Memorial Fellowship Fund, founded by Mikhail Baryshnikov with Brodsky’s family to honor the poet, please visit josephbrodsky.org.

Henry Romero/Reuters

Billionaires Bill Gates and Carlos Slim at the opening of a new research facility for the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, Texcoco, Mexico, February 2013

Henry Romero/Reuters

Billionaires Bill Gates and Carlos Slim at the opening of a new research facility for the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center, Texcoco, Mexico, February 2013

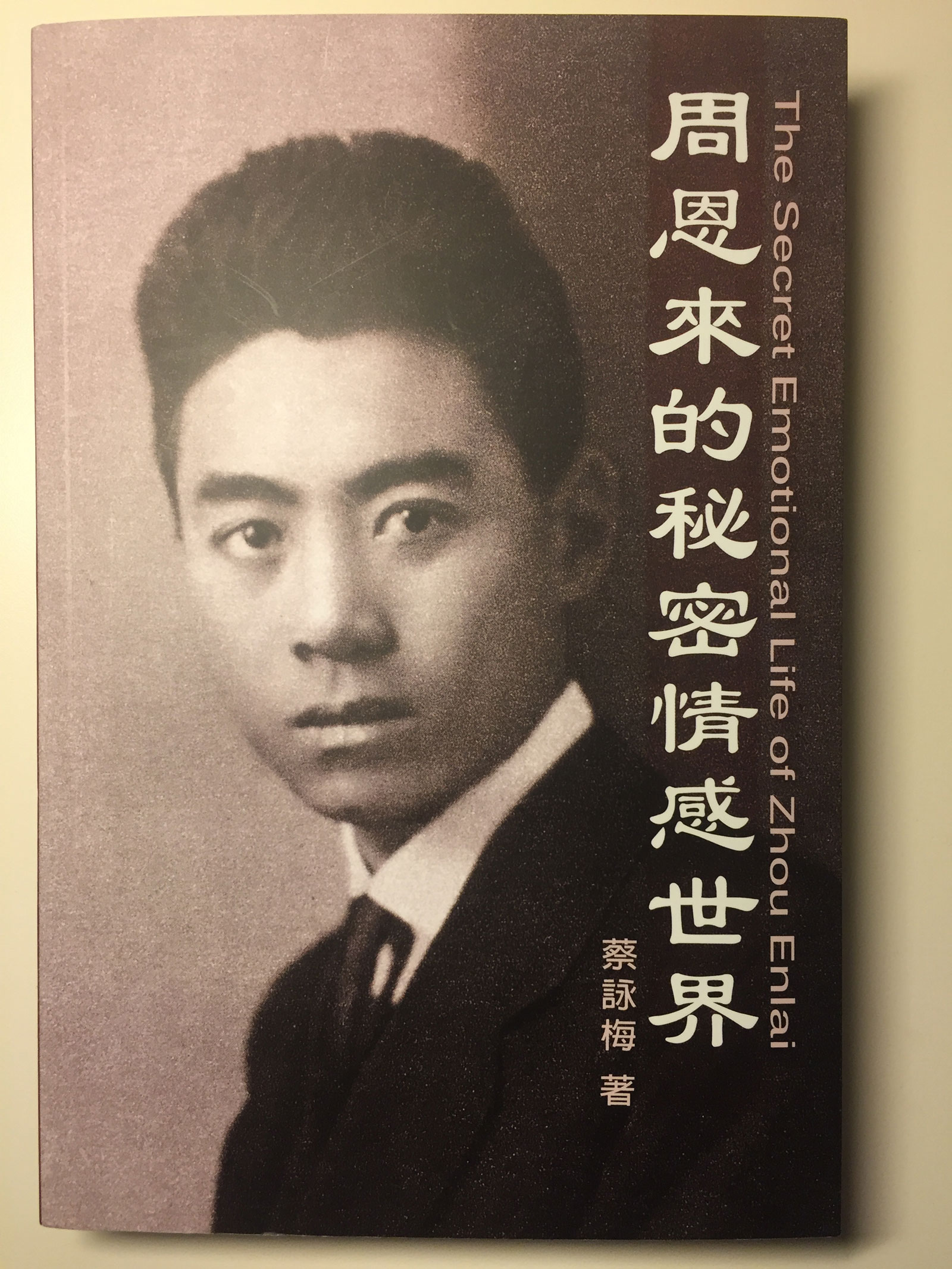

George Grosz: Streetcafé, 1917

George Grosz: Streetcafé, 1917

Christian Liewig/Liewig Media Sports/Corbis

The renovated Rodin Museum in Paris, which reopened to the public on November 12, 2015, on the 175th anniversary of Rodin’s birth. At right is Rodin’s sculpture The Three Shades (before 1886).

Christian Liewig/Liewig Media Sports/Corbis

The renovated Rodin Museum in Paris, which reopened to the public on November 12, 2015, on the 175th anniversary of Rodin’s birth. At right is Rodin’s sculpture The Three Shades (before 1886).

Pablo Enriquez/Museum of Modern Art, New York

Works by Pablo Picasso in the exhibition ‘Picasso Sculpture’ at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, 2015

Pablo Enriquez/Museum of Modern Art, New York

Works by Pablo Picasso in the exhibition ‘Picasso Sculpture’ at the Museum of Modern Art, New York City, 2015

Museum of Modern Art, New York/© 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso: Glass of Absinthe, spring 1914

Museum of Modern Art, New York/© 2015 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Pablo Picasso: Glass of Absinthe, spring 1914

Musée Thomas Henry, Cherbourg, France/Bridgeman-Giraudon/Art Resource

Fra Angelico: The Conversion of Saint Augustine, circa 1430s

Musée Thomas Henry, Cherbourg, France/Bridgeman-Giraudon/Art Resource

Fra Angelico: The Conversion of Saint Augustine, circa 1430s

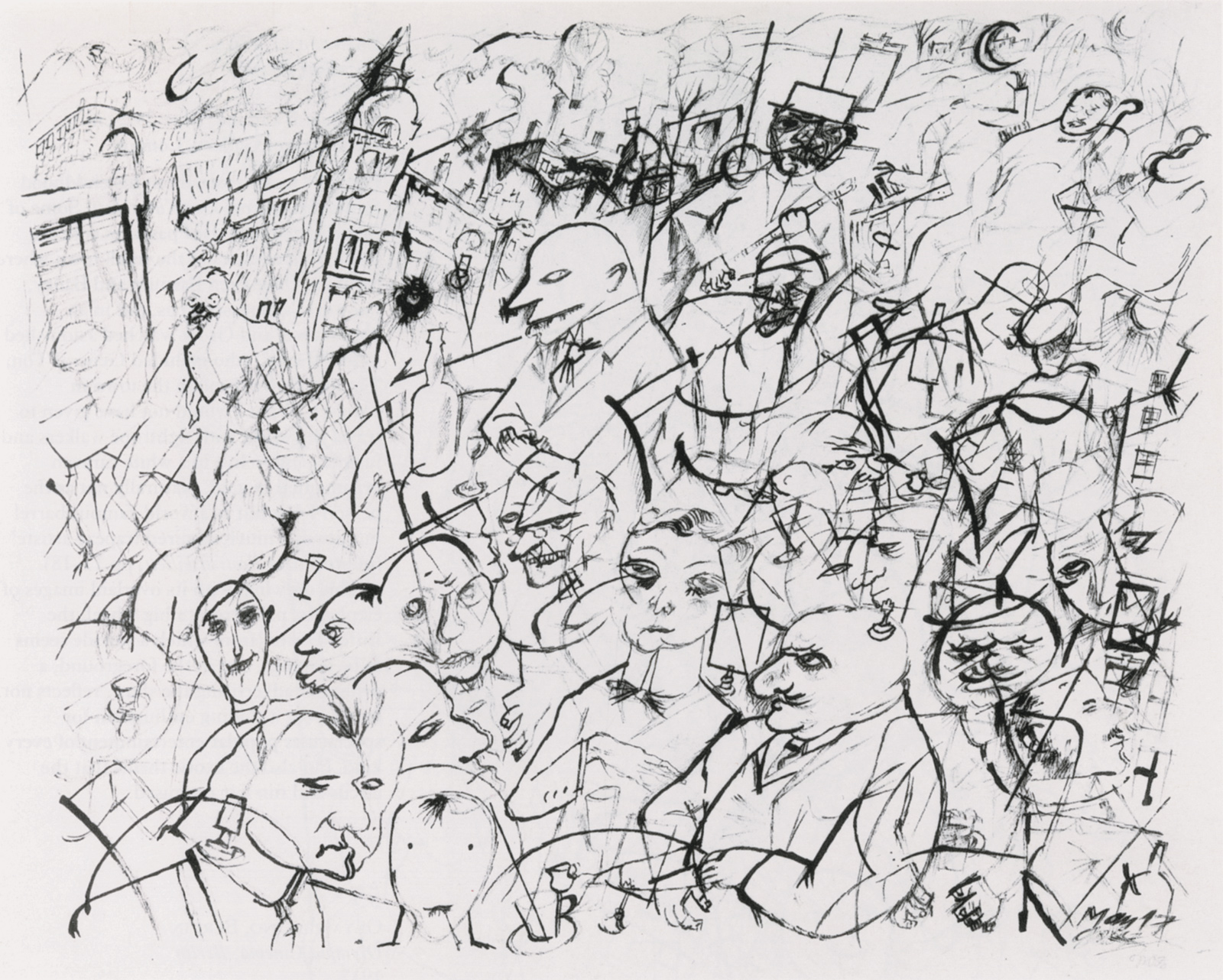

Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris/Scala/White Images/Art Resource‘Saint Augustine writing’; illumination from Augustine’s City of God, 1459

Bibliothèque Sainte-Geneviève, Paris/Scala/White Images/Art Resource‘Saint Augustine writing’; illumination from Augustine’s City of God, 1459

Reg Innell/Toronto Star/Getty Images

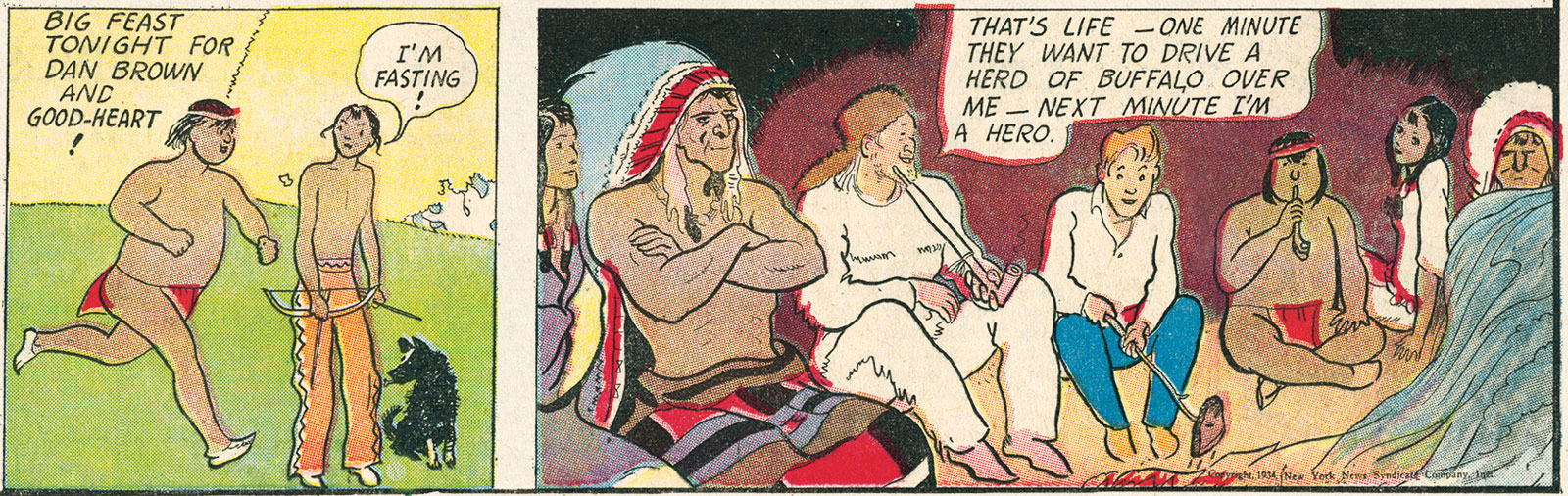

Joy Williams, 1990

Reg Innell/Toronto Star/Getty Images

Joy Williams, 1990

Edward Gorey Charitable Trust

Drawing by Edward Gorey

Edward Gorey Charitable Trust

Drawing by Edward Gorey

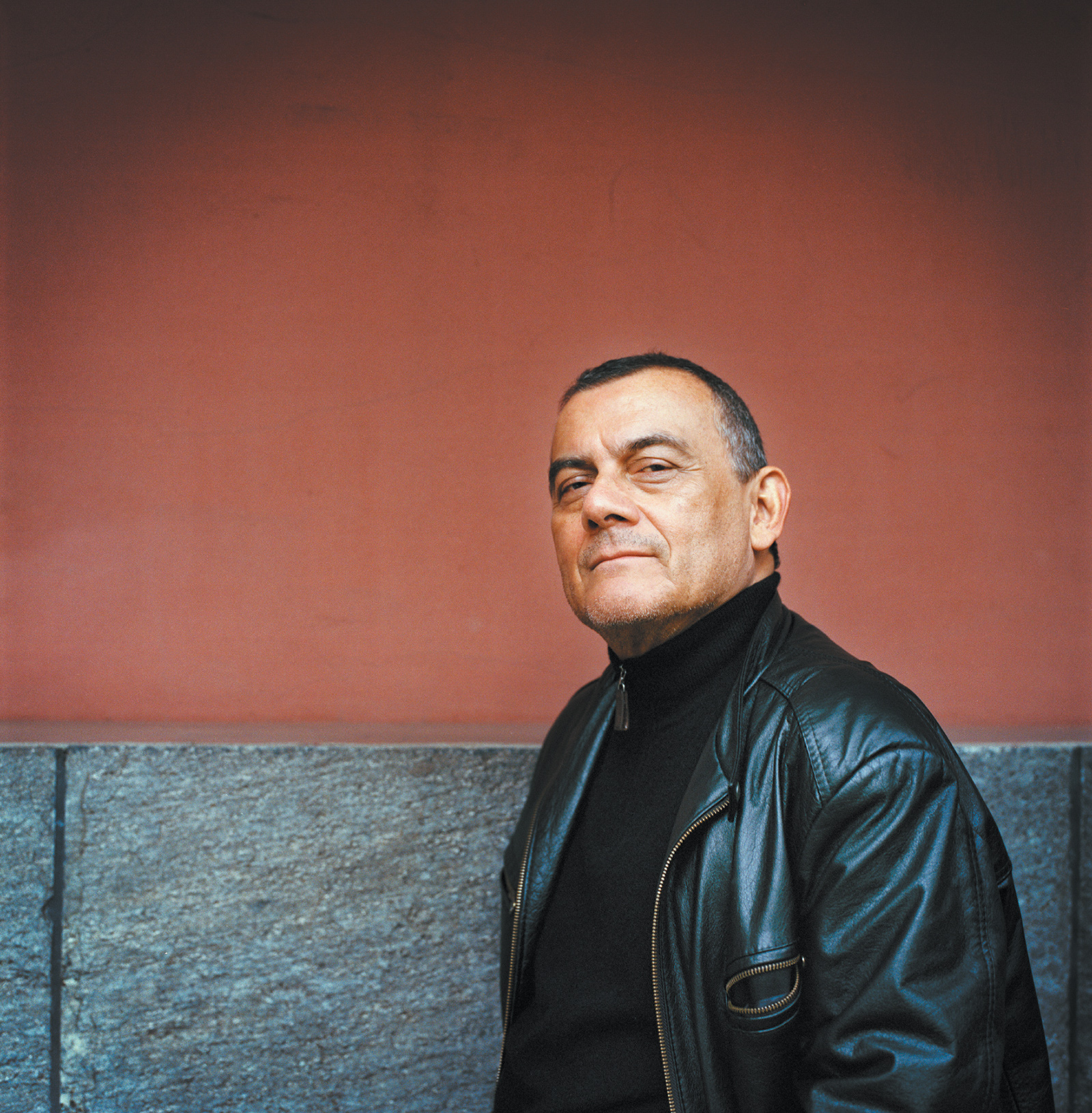

Gunter Gluecklich/Iaif/Redux

Horacio Castellanos Moya, 2015

Gunter Gluecklich/Iaif/Redux

Horacio Castellanos Moya, 2015

Larry Towell/Magnum Photos

New recruits to the El Salvadoran army learning to assemble and disassemble US-made M16 assault rifles, San Miguel, El Salvador, 1988

Larry Towell/Magnum Photos

New recruits to the El Salvadoran army learning to assemble and disassemble US-made M16 assault rifles, San Miguel, El Salvador, 1988