The Complete Stories![]()

by Clarice Lispector, translated from the Portuguese by Katrina Dodson, edited and with an introduction by Benjamin Moser

New Directions, 645 pp., $28.95

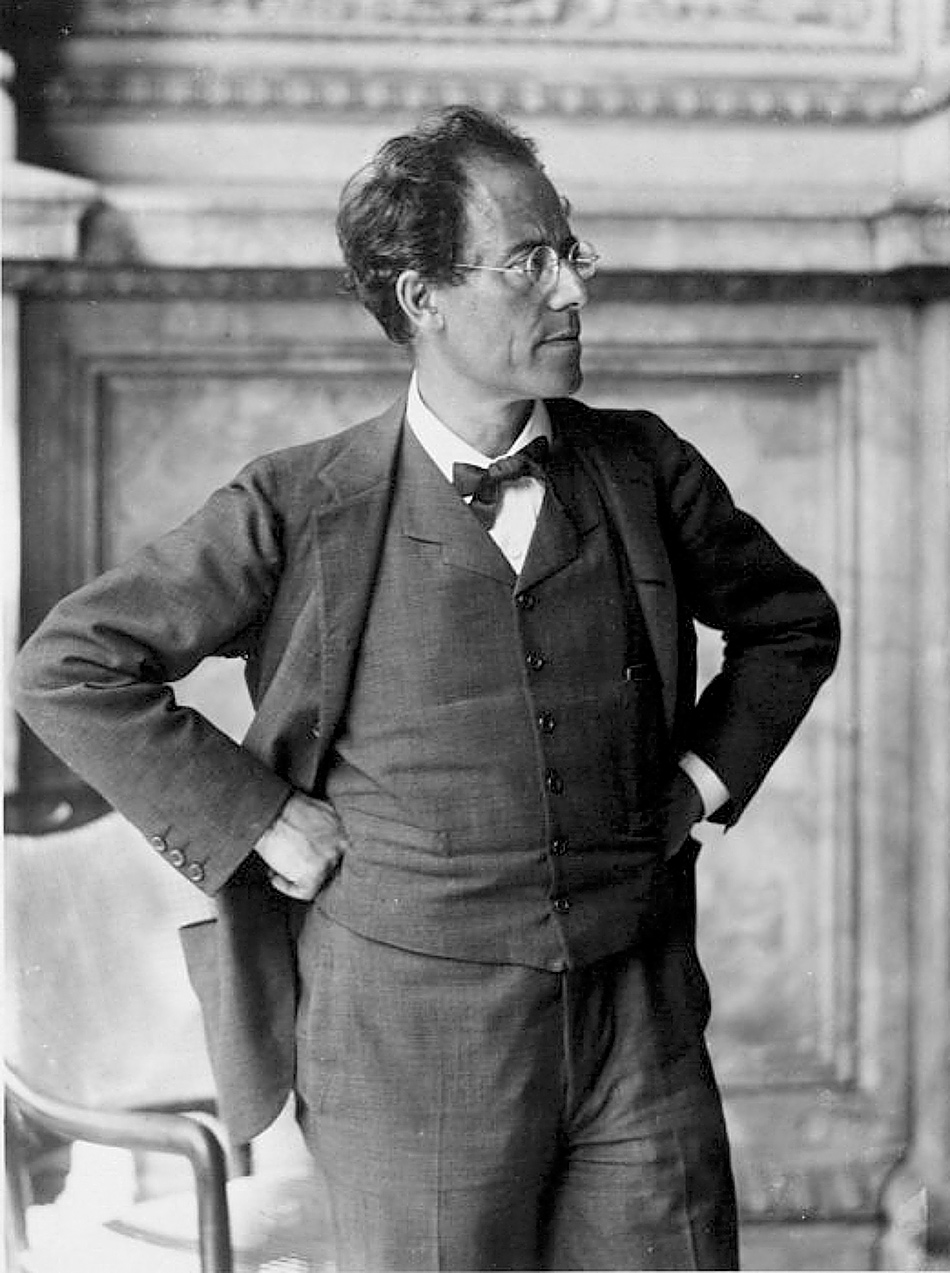

Clarice Lispector; drawing by Pancho

Clarice Lispector; drawing by Pancho

In Chapter Six of his novel Murphy, Samuel Beckett considered what he called “Murphy’s mind”:

Murphy’s mind pictured itself as a large hollow sphere, hermetically closed to the universe without. This was not an impoverishment, for it excluded nothing that it did not itself contain. Nothing ever had been, was or would be in the universe outside it but was already present as virtual, or actual, or virtual rising into actual, or actual falling into virtual, in the universe inside it.

In Beckett’s fiction, there is a sense that the spirit of his characters is elsewhere, hidden from their bodies. They may know how to think, but the notion that this leads them therefore to exist is a sour joke. The word “therefore” in the Cartesian equation has been somehow mislaid. Their bodies, in all their frailty and levels of discomfort, tell his characters that they are alive. This knowledge is made more comic and tragic and indeed banal by the darting quality of the minds of many of Beckett’s characters, by the amount of nonsense going on in their heads. They are like hens pecking at memory and experience.

Hens are dear to the strange, bitter heart of the Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector. Their general helplessness combined with their persistence, their constant pecking and mindless squawking, seemed to animate something in her spirit. During her childhood in the north of Brazil, according to her biographer Benjamin Moser, “she spent hours with the chickens and hens in the yard.” “I understand a hen, perfectly,” she told an interviewer. “I mean, the intimate life of a hen. I know how it is.” One of her finest stories is “A Chicken,” three pages long, which tells of a bird trapped in a kitchen waiting to be sacrificed for Sunday lunch who decides to make a brief, defiant flight, only to be chased by the man of the house. “From rooftop to rooftop they covered more than a block. Ill-adapted to a wilder struggle for life, the chicken had to decide for herself which way to go, without any help from her race.”

The day is saved, or at least the chicken is, when she lays an egg and it is decided not to cook her, but instead to include her in the household. Thus

whenever everyone in the house was quiet and seemed to have forgotten her, she would fill up with a little courage, vestiges of the great escape—and roam around the tiled patio, her body following her head, pausing as if in a field, though her little head gave her away: vibratory and bobbing rapidly, the ancient fright of her species long since turned mechanical.

Lispector, however, has no interest in allowing this triumph to be more than brief. In a brisk and sudden final sentence, she does away with her brave bird: “Until one day they killed her, ate her and years went by.”

In a later story, “A Tale of So Much Love,” the figure of the chicken will reappear with even more human qualities. It begins: “Once upon a time there was a little girl who observed chickens so closely that she got to know their souls and innermost yearnings.” As the chicken is being eaten by the family, Lispector comments: “Chickens seem to have a prescience about their own fate and they never learn to love either their owners or the rooster. A chicken is alone in the world.”

Lispector also wrote a story, or a meditation, called “The Egg and the Chicken,” in which she ponders the great matter of Being from the perspective of chicken and egg:

The egg is the chicken’s great sacrifice. The egg is the cross the chicken bears in life. The egg is the chicken’s unattainable dream. The chicken loves the egg. She doesn’t know the egg exists. If she knew she had the egg inside her, would she save herself? If she knew she had the egg inside her, she would lose her state of being a chicken. Being a chicken is the chicken’s survival. Surviving is salvation. For living doesn’t seem to exist. Living leads to death…. Surviving is what’s called keeping up the struggle against life that is deadly. That’s what being a chicken is.

Besides chickens, Lispector was interested in rats. In “Another Couple of Drunks,” the narrator conjures up the aftermath of the death of a child:

The household rats take fright and start to race around the room. They crawl up your son’s face, still warm, gnaw at his little mouth. The woman screams and faints, for two hours. The rats visit her body too, cheerful, nimble, their tiny teeth gnawing here and there…. She looks around, gets up and the rats scatter.

In “Preciousness,” the girl recalls that when she was ten “a boy with a crush on her had thrown a dead rat at her.” In an essay on Brasília, included in this book as a story—it is a sort of story, but perhaps, as with many of these stories, it could be better defined as a strange display of sensibility—Lispector writes:

It was built with no place for rats. A whole part of us, the worst, precisely the one horrified by rats, that part has no place in Brasília. They wished to deny that we are worthless. A construction with space factored in for the clouds. Hell understands me better. But the rats, all huge, are invading.

If Brasília has no place for rats, then Rio de Janeiro, where many of these stories are set, has plenty of such spaces. In “Forgiving God,” the narrator of the story, who feels that she is “the mother of God” while walking down Avenida Copacabana,

almost stepped on a huge dead rat. In less than a second I was bristling from the terror of living, in less than a second I was shattering in panic, and doing my best to rein in my deepest scream. Nearly running in fright, blind in the midst of all those people, I wound up on the next block leaning on a pole, violently shutting my eyes, which no longer wanted to see. But the image stuck to my eyelids: a big red-haired rat, with an enormous tail, its feet crushed, and dead, still, tawny. My boundless fear of rats.

If rats then represent terror and chickens innocent striving for something approaching authenticity, humans, for Lispector, are strangely in the middle, often stricken with fear, or handing out terror, but ready also to soar or break loose or achieve some freedom or be fully alert to their fate in a time short enough for one of her stories to be enacted.

Clarice Lispector was born in Ukraine in 1920 and taken to Brazil as an infant. Raised in Recife, the north of the country, she married a diplomat and thus spent many years traveling before returning to Brazil to live in Rio de Janeiro. In 1966 she was badly injured in a fire in her apartment. She died in 1977.

By the time of her death, she had become, Benjamin Moser writes in his biography of her, “one of the mythical figures of Brazil, the Sphinx of Rio de Janeiro, a woman who fascinated her countrymen virtually from adolescence.”* Her looks were often commented on and there was much gushing nonsense written about her. The translator Gregory Rabassa, for example, recalled being “flabbergasted to meet that rare person who looked like Marlene Dietrich and wrote like Virginia Woolf.” The poet Ferreira Gullar remarked that “she looked like a she-wolf, a fascinating wolf.” And the French critic Hélène Cixous declared that Lispector was what Kafka would have been had he been a woman, or “if Rilke had been a Jewish Brazilian born in the Ukraine. If Rimbaud had been a mother, if he had reached the age of fifty. If Heidegger could have ceased being German.”

While Lispector did not refer much in public to her family’s origins, they are made grimly clear in Moser’s biography. “The least one can say about the time and place of her birth,” he writes,

is that they were badly chosen…. What befell the Jews of the Ukraine around the time of Clarice Lispector’s birth was a disaster on a scale never before imagined. Perhaps 250,000 were killed: excepting the Holocaust, the worst anti-Semitic episode in history.

It may be too easy to explain the sort of estrangement that distinguishes the work of Lispector as arising from her family’s history and her own early years in Brazil, years marked by her mother’s slow death from syphilis, caused by her having been raped before the family fled Ukraine. Her mother died in 1930 when Lispector was ten. Her father died a decade later.

The peculiar tone of her work takes its bearings equally perhaps from the Brazilian literary tradition itself, from figures such as Machado de Assis (1839–1908), whom she read as a teenager, and her contemporary João Guimarães Rosa (1908–1967), whom she admired. Neither of these writers was concerned with holding a mirror up to Brazilian society, but rather they were involved in breaking the mirror of fiction itself, creating images of estrangement in works that were formally experimental and ambitious, using tones that seemed to have no antecedents, remaking a tradition in their own brittle image. When Lispector began to write, it might have seemed almost natural for her to create stories that were often abstract, unhinged, haunted, highly peculiar, dealing with figures who were isolated, damaged, and, like the mind of Beckett’s Murphy, “hermetically closed to the universe without.”

In her mixture of nonchalance, inscrutability, wit, and knowing simplicity, in her use of tones that are whimsical and subtle, in the stories that are filled with abstractions, she has perhaps more in common with some Brazilian visual artists of her generation than she does with any writers, most notably Lygia Clark, who was born in the same year as Lispector, and also Hélio Oiticica, who both used minimal means and often flat color to create works of considerable intensity and oddness.

Between 1943, when her first book was published, and her death, Lispector produced nine novels, nine volumes of stories, some children’s writing, and a good deal of journalism. In her stories the range is limited; her subject mainly is fearfulness in the lives of women, the fraught interior of the mind, the fragility of the domestic sphere, the ghostliness of the self. Her figures are unnerved by the world, its rituals and regulations; they are often frightened by interaction with others. They ask small questions but there is always the sense that the answers might turn out to be much larger, or more disquieting, than any of her characters have bargained for.

Thus she builds by a system of erasure. Social and political questions do not interest her, or the creation of three-dimensional figures, or characters whose motives make full sense or evoke easy sympathy, or indeed the natural world. In comparing the city of Brasília to “a beach without the sea,” she could be describing the unsettling nature of her own writing, her own use of palpable absences. She works with much that is missing, eschewing the obvious for the sake of what becomes in the best stories a sort of penetrating emotional effect.

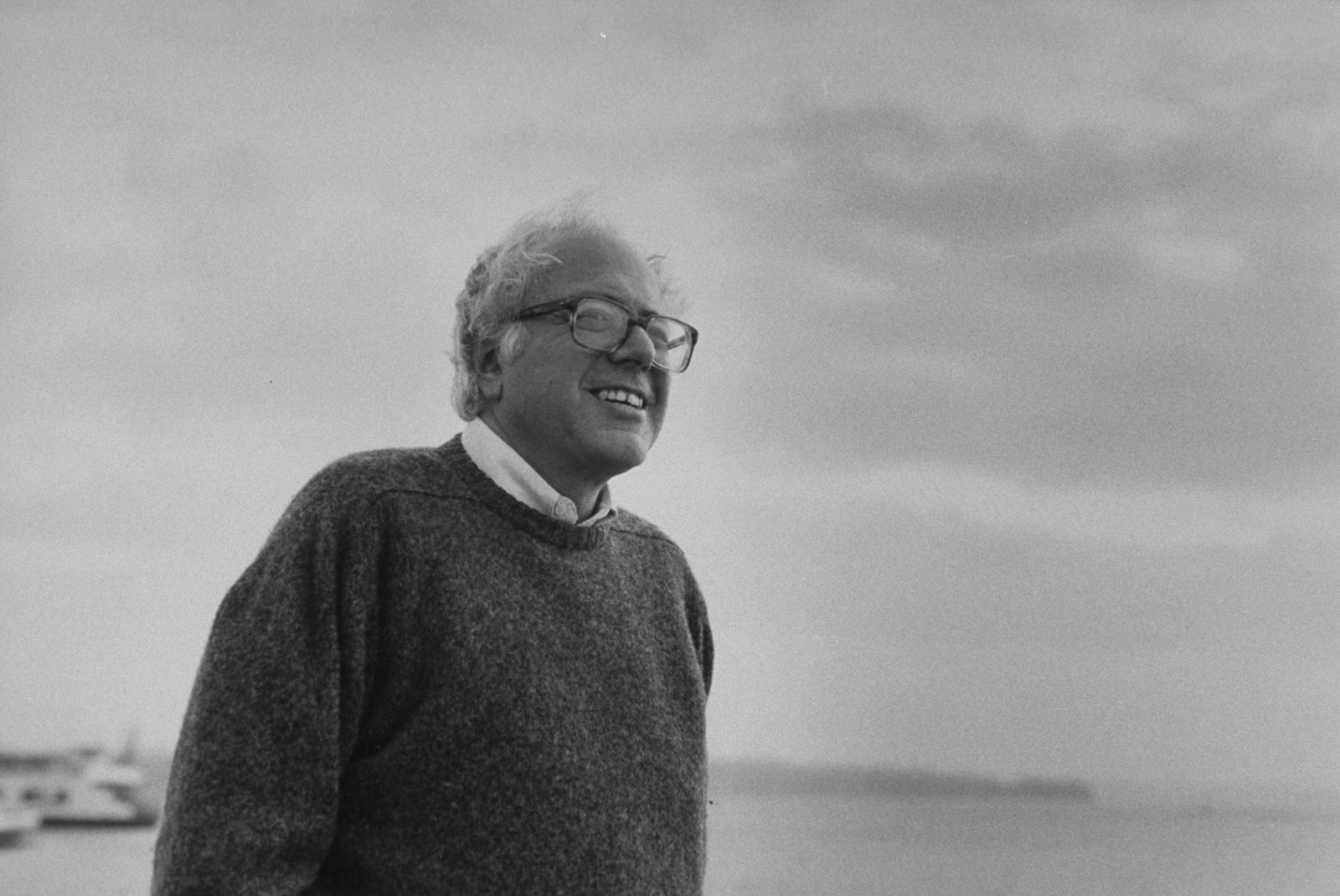

Alair Gomes

Clarice Lispector, Rio de Janeiro, circa 1969

Alair Gomes

Clarice Lispector, Rio de Janeiro, circa 1969

Some of her openings are startling. The first paragraph of “Interrupted Story,” for example, begins:

He was sad and tall. He never spoke to me without making it understood that his gravest flaw lay in his tendency toward destruction. And that was why, he’d say, stroking his black hair as if stroking the soft, hot fur of a kitten, that was why his life amounted to a pile of shards: some shiny, others clouded, some cheerful, others like a “piece of a wasted hour,” meaningless, some red and full, others white, but already shattered.

Here she seems more fascinated by the words and the phrases themselves, and by creating a tone, than by any events that will subsequently unfold. She likes stories in which nothing, or nothing much, happens. “Excerpt” begins: “Really nothing happened on that gray afternoon in April.” She also likes creating an opening sentence of direct and startling color, such as the opening of “Temptation”: “She was sobbing. And as if the two o’clock glare weren’t enough, she had red hair.” Or the opening sentence of “The Solution”: “Her name was Almira and she’d grown too fat.” Or the even more vivid and startling opening of the story “Better Than to Burn”: “She was tall, strong, hairy.”

Her women are easily disturbed, thus self-contained by necessity. In “The Imitation of the Rose,” Laura realizes that

she must never again give cause for alarm…. And most important of all was sparing everyone from suffering the least bit of doubt. And to never again cause other people to fuss over her….

Men are often a mystery. In “The Escape”:

Her gaze starts evoking a deep well. Dark and silent water. Her gestures go blank but she has but one fear in life: that something will come along and transform her…. Desires are ghosts that dissolve as soon as you light the lamp of good sense. Why is it that husbands are good sense? Hers is particularly solid, good, and never wrong.

Her women often stay in bed. Home life puzzles them as they venture away from the domestic sphere toward some other realm, almost eschatological in its contours, as in the story “Love”:

When she returned it would be the end of the afternoon and the children home from school needed her. In this way night would fall, with its peaceful vibration. In the morning she’d awake haloed by her calm duties. She’d find the furniture dusty and dirty again, as if repentantly come home. As for herself, she obscurely participated in the gentle black roots of the world. And nourished life anonymously. That was what she had wanted and chosen.

In “The Sound of Footsteps,” Mrs. Cândida Raposo, who is eighty-one, goes to the doctor because she still feels “the desire for pleasure.” The doctor agrees that one solution might be if she “took care of it” herself. “That same night she found a way to satisfy herself on her own. Mute fireworks.” Then the next paragraph comes straight from Lispector’s personal lexicon of disappointment, with its own half-resigned diction: “Afterward she cried. She was ashamed. From then on she’d use the same method. Always sad. That’s life, Mrs. Raposo, that’s life. Until the blessing of death.”

Lispector had no interest in blessing, or happiness for that matter. Rather, she entertained happiness so she could play with it, leave scratch marks on it, wound it as best she could. Thus “Happy Birthday,” one of her finest stories, will deal with a birthday that is considerably less than happy. The woman whose birthday it is—she is eighty-nine—has to cut the cake. “And suddenly the old woman grabbed the knife. And without hesitation, as if in hesitating for a moment she might fall over, she cut the first slice with a murderer’s thrust.”

Slowly, the old lady begins to loathe her children who have gathered with their own families for this festive occasion:

How could she have given birth to those frivolous, weak, self-indulgent beings? The resentment rumbled in her empty chest. A bunch of communists, that’s what they were; communists. She glared at them with her old woman’s ire. They looked like rats jostling each other, her family. Irrepressible, she turned her head and with unsuspected force spat on the ground.

Objects and flowers, in Lispector’s worldview, fare no better than people. “The last light of the afternoon was heavy and beat down solemnly on the objects.” Hyacinths are “rigid against the windowpane.” Even teeth get it in the neck, a mouthful of them being referred to as “the misplaced cruelty of teeth.” And speaking of getting it in the neck, in “The Solution” Almira stabs her friend Alice in the neck with a fork in a restaurant for no apparent reason, or perhaps to make sure that the reader is paying full attention, or perhaps even to allow Lispector to write the next sentence, which sounds beautiful in Katrina Dodson’s translation: “The restaurant, according to the newspaper, rose as one.”

While some stories appear whimsical and read like exercises, and others muse at length and almost absent-mindedly, almost abstractly, on habit and motive, or something that happened, others have an exquisite sharpness, the fruit of a most original and daring mind. In the best stories, something deeply strange is fully visualized by Lispector, as though it had come in a waking dream and it needed to be given urgent substance. “Mystery in São Cristóvão,” for example, begins with the sort of domestic scene that is always ominous in Lispector’s universe. A family is having a meal together. “There was nothing special about the gathering; they had just finished dinner and were chatting around the table, mosquitoes circling the light.”

Then they go to sleep, and from a house on the corner emerge three figures, as though from a James Ensor painting:

One was tall and had on the head of a rooster. Another was fat and had dressed as a bull. And the third, who was younger, for lack of a better idea, had disguised himself as a lord from olden times and put on a devil mask, through which his innocent eyes showed.

As they set about stealing some hyacinths from the garden of the family who have previously been eating together, “from behind the dark glass of the window a white face was staring at them.” It is the daughter of the house. Lispector now moves into a strange, luminous fictional terrain, lifting the drama with ghostly precision high above its own cause. When the moon appears

it was a stroke of danger for the four visages. So risky that, without a sound, four mute visions retreated without taking their eyes off each other, fearing that the moment they no longer held each other’s gaze remote new territories would be ravaged….

The experience briefly ages the girl, but then, in the last paragraph:

The girl gradually recovered her true age. She was the only one not constantly peering around. But the others, who hadn’t seen a thing, grew watchful and uneasy. And since progress in that family was the fragile product of many precautions and a handful of lies, everything came undone and had to be remade almost from scratch….

Some of Lispector’s images are deeply grotesque. In “The Smallest Woman in the World”—originally translated by Elizabeth Bishop, who knew Lispector in Brazil—something whimsical slowly becomes oddly real and disturbing. It includes, as an aside, a story the cook told “about her time at the orphanage” when the girls, who had no dolls to play with, concealed the death of a fellow inmate from the nuns. “They hid the corpse in a wardrobe until the nun left, and played with the dead girl, giving her baths and little snacks, punishing her just so they could kiss her afterward, consoling her.”

In “The Crime of the Mathematics Teacher,” a man buries a dead dog only to unbury the creature in the final paragraph for no reason that is fully clear. The last two sentences read: “The man then looked around and to the heavens beseeching a witness to what he had done. And as if that still weren’t enough, he started descending the slopes toward the bosom of his family.” It is easy to hear the grim laughter here, as though the bosom of his family were somehow more transcendental or more scary than the heavens.

Lispector’s command of tone allows her to be amused gently and with subtlety at times, at other times savagely, and then at other times, in the weakest stories, she creates a story with a throwaway tone, as though she could not really be bothered. In “Via Crucis,” for example, a virgin gets pregnant. In one paragraph, the young woman treats the event as though it is ordinary. “Maria das Dores sent the maid out to buy the vitamins the gynecologist had prescribed. They were for her son’s benefit.” In the following paragraph, the pregnant virgin has another thought: “Divine son. She had been chosen by God to give the world the new Messiah.” And then: “She bought a blue cradle. She started knitting little jackets and making cloth diapers.”

God makes strange appearances in these stories. In “Report on the Thing,” a late story:

God has no name: he preserves perfect anonymity: there is no language that utters his true name….

I am now going to say a very serious thing that will seem like heresy: God is dumb. Because he does not understand, he does not think, he just is…. But He commits many errors. And knows it. Just look at us who are a grave error. Just look how we organize ourselves into society and intrinsically, from one to another. But there is one error He does not commit: He does not die.

In another late story, Lispector invokes the famous image of Christ with his outstretched arms on the hill of Corcovado overlooking Rio de Janeiro: her main character

had the oddest dream: she dreamed she saw the Christ on Corcovado—and where were his outstretched arms? They were tightly crossed, and Christ looked fed up as if to say: deal with it yourselves, I’ve had it. It was a sin, that dream.

And then in her meditation on Brasília, God is also mentioned:

Brasília is artificial. As artificial as the world must have been when it was created. When the world was created, a man had to be created especially for that world. We are all deformed by our adaptation to the freedom of God. We don’t know how we would be if we had been created first and the world were deformed after according to our requirements.

The state of being deformed spiritually or ontologically interested Lispector. She let her imagination range over its fictional possibilities. She dramatized it in some stories by lifting restrictions on her characters to see what they would do. In other stories, she became interested in the thin and brittle nature of the self and in what she called “the destiny of those set loose upon the Earth, of those who don’t measure their actions according to Good and Evil.”

She was, all the time, ruefully aware of the limitations that writing imposed on her. Part of her dark vision included a sad knowledge of the frailty of the very words and phrases she used, the necessary thinness of her own observations and her games with form. Thus the images of the chicken and the rat were useful to her in that they carried more meaning with them, more weight somehow, than many of her images of human striving. In an early story, she allowed her main character to feel this helplessness deeply and articulate as best she could the idea, as Beckett would have it, that she was resigned to fail better, but fail nonetheless:

Something beneath my thought, deeper and stronger, apprehends what happened and, in a fleeting instant, I see it clearly. But my brain is feeble and I can’t manage to transform that vivid minute into thought.

Such a feeling and such failure would have been, oddly enough, deeply satisfying for Lispector, and easy for her to imagine, part of the shadow world she attempted to find pale and unsettling substance for in these stories.

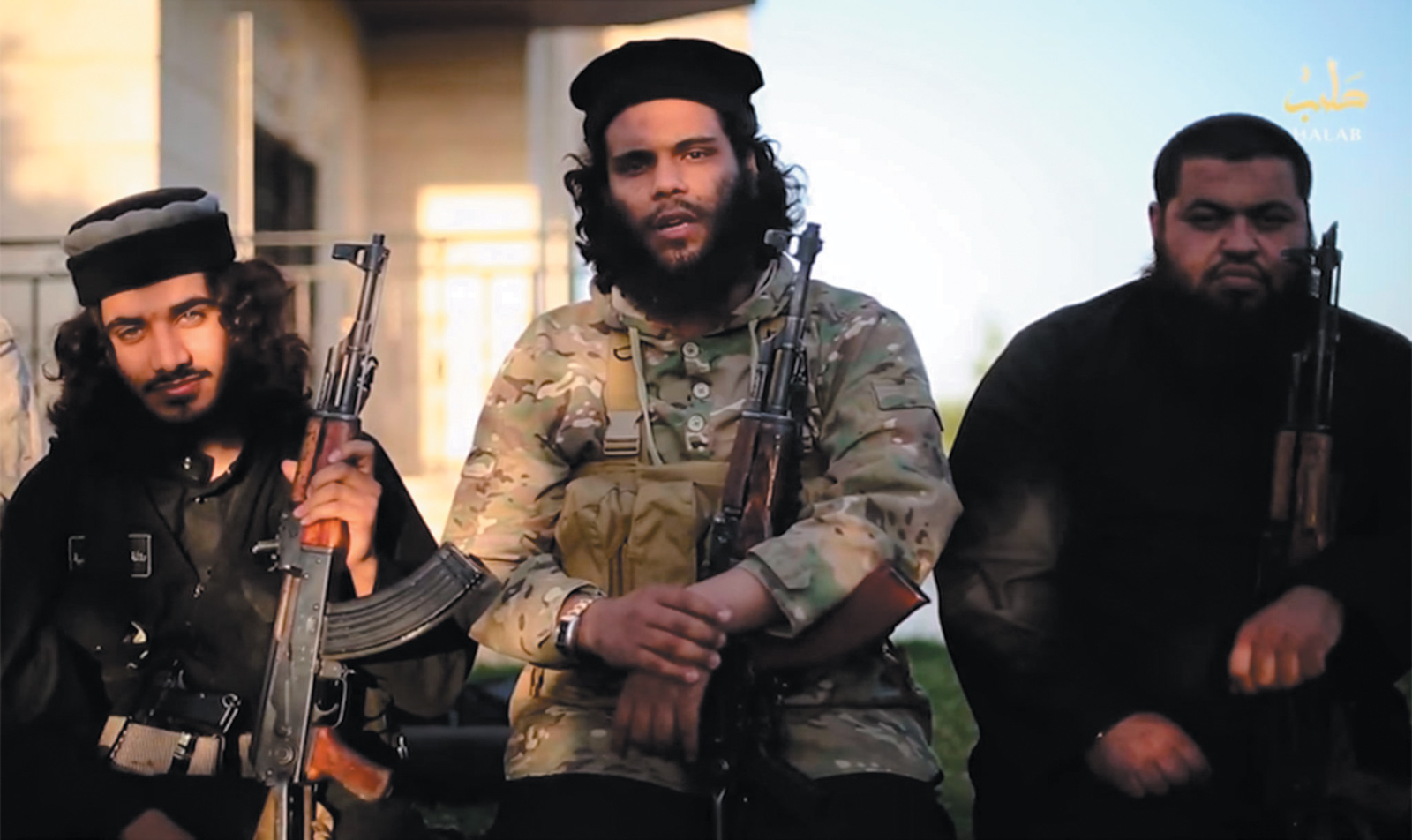

A still from a video released by ISIS militants in June 2015 called ‘A Message to Our People in Jerusalem,’ in which they threaten to overthrow Hamas in Gaza because the group is not extreme enough

A still from a video released by ISIS militants in June 2015 called ‘A Message to Our People in Jerusalem,’ in which they threaten to overthrow Hamas in Gaza because the group is not extreme enough

jaminwell/E+/Getty Images

A beach in the Virgin Islands, which, along with countries like Switzerland and Luxembourg, are a notorious tax haven for the wealthy

jaminwell/E+/Getty Images

A beach in the Virgin Islands, which, along with countries like Switzerland and Luxembourg, are a notorious tax haven for the wealthy

Vincent Kessler/Reuters

Members of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France, holding signs in support of a motion to censure the European Commission under Jean-Claude Juncker because of the aggressive tax-avoidance policies pursued by Luxembourg while Juncker was prime minister, November 2014

Vincent Kessler/Reuters

Members of the European Parliament in Strasbourg, France, holding signs in support of a motion to censure the European Commission under Jean-Claude Juncker because of the aggressive tax-avoidance policies pursued by Luxembourg while Juncker was prime minister, November 2014

Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne, Switzerland

Auguste Forestier: Untitled, circa 1935–1951

Collection de l’Art Brut, Lausanne, Switzerland

Auguste Forestier: Untitled, circa 1935–1951 MoMA/Nina and Gordon Bunshaft Fund

Jean Dubuffet: Wall with Inscriptions, 1945

MoMA/Nina and Gordon Bunshaft Fund

Jean Dubuffet: Wall with Inscriptions, 1945 MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. Ralph F. Colin

Jean Dubuffet: Bird Perched on the Corner of the Wall, 1945

MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. Ralph F. Colin

Jean Dubuffet: Bird Perched on the Corner of the Wall, 1945 MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. Ralph F. Colin

Jean Dubuffet: Profile of a Man's Head in Front of a Wall, 1945

MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. Ralph F. Colin

Jean Dubuffet: Profile of a Man's Head in Front of a Wall, 1945 MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. N. Richard Miller Fund; Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman Fund; Samuel Girard Fund

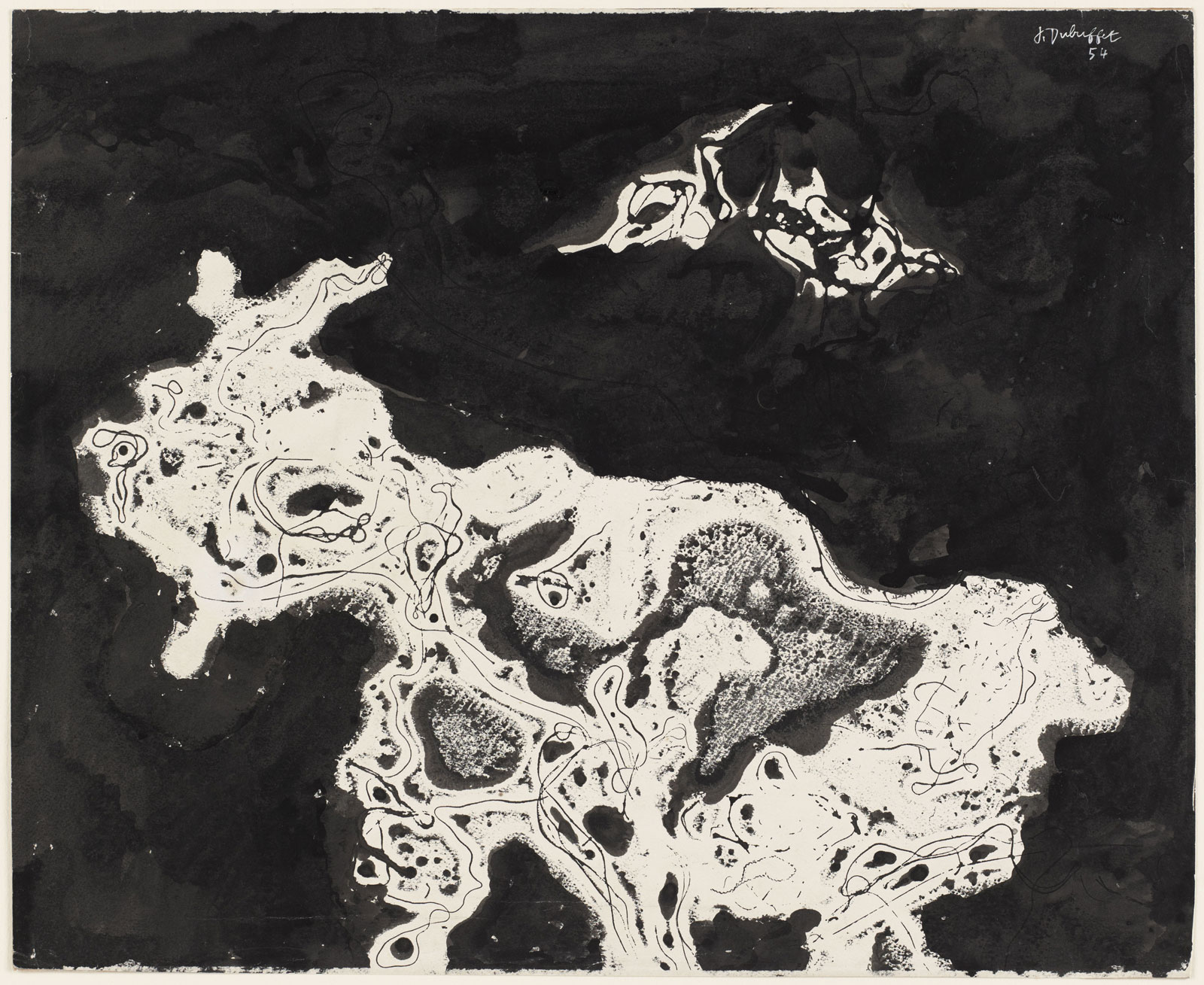

Jean Dubuffet: The Magician, 1954

MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. N. Richard Miller Fund; Mr. and Mrs. Alex L. Hillman Fund; Samuel Girard Fund

Jean Dubuffet: The Magician, 1954 MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. Donald H. Peters

Jean Dubuffet: Black Earth, 1955

MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. Donald H. Peters

Jean Dubuffet: Black Earth, 1955 MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. Ralph F. Colin Fund/Philip Johnson

Jean Dubuffet: Soil Ornamented with Vegetation, Dead Leaves, Pebbles, Diverse Debris, 1956

MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. Ralph F. Colin Fund/Philip Johnson

Jean Dubuffet: Soil Ornamented with Vegetation, Dead Leaves, Pebbles, Diverse Debris, 1956 MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. Ralph F. Colin

Jean Dubuffet: Pavement of Skin, 1958

MoMA/Mr. and Mrs. Ralph F. Colin

Jean Dubuffet: Pavement of Skin, 1958 MoMA/Mrs. Sam A. Lewisohn Fund

Jean Dubuffet: Beard of Uncertain Returns, 1959

MoMA/Mrs. Sam A. Lewisohn Fund

Jean Dubuffet: Beard of Uncertain Returns, 1959 MoMA/Mary Sisler Bequest

Jean Dubuffet: Soul of the Underground, 1959

MoMA/Mary Sisler Bequest

Jean Dubuffet: Soul of the Underground, 1959 MoMA/Nina and Gordon Bunshaft Bequest

Jean Dubuffet: Beard Wine, 1959

MoMA/Nina and Gordon Bunshaft Bequest

Jean Dubuffet: Beard Wine, 1959